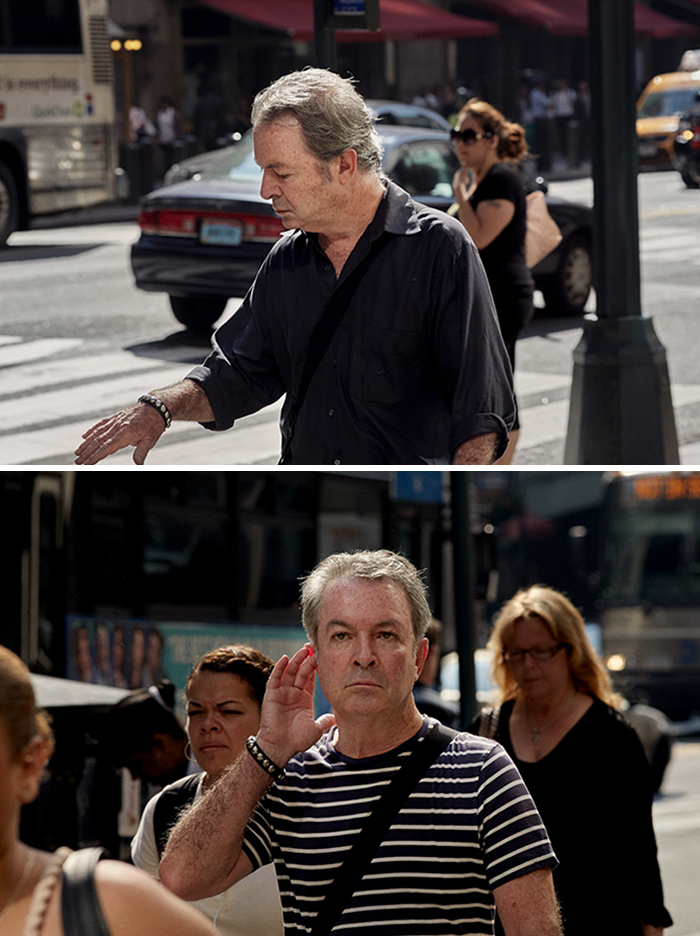

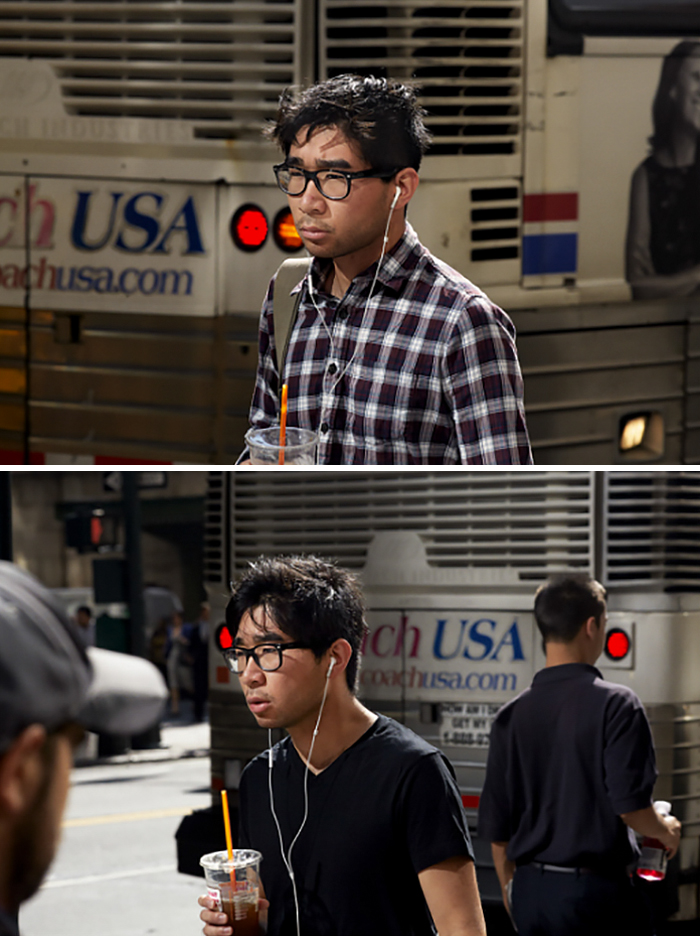

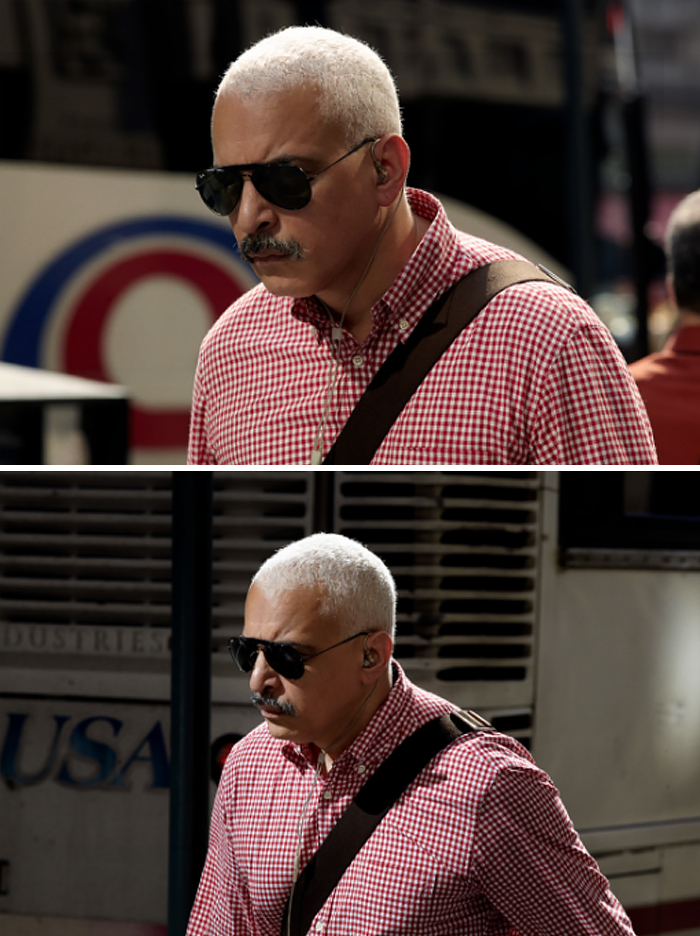

For 9 years, from 8:30 am and 9:30 am, Danish photographer Peter Funch stood at the southern corner of 42nd Street and Vanderbilt Avenue. In the rush of commuters, what he found was a glimpse of universal habits and the long trek to work. From 2007 to 2016 Funch carried out his project 42nd and Vanderbilt in which he captures the same person twice, mid-commute, leaving the viewer to wonder if they were photographed days, months, or even years apart.

The work of Peter Funch is, in the most captivating sense of the term, lost in time. It seems like the sort of work Andy Warhol might be doing now were he still alive. It’s twenty-first century yet 1970s. It’s metropolitan, cosmopolitan and simultaneously inhabits any number of art niches: social sculpture, time-based-art, and portraiture. As well, it feels creepy and stalkery in a very nice way… a kinder, gentler kind of surveillance.

Looking at the photos I can’t help but wonder if any of their New Yorker subjects would see them and, a) be attered, b) feel stalked, c) be proud or, d) sue. But then you couldn’t really sue Funch. He is a documentarian and he has a stunning eye for capturing the golden needle in the haystack of daily life. He also highlights the somewhat industrialized nature of the everyday downtown work cycle. Who are these people? Are they not aware that they’ve become clichés of themselves? But then what’s wrong with being your own cliché — what sort of judgment system would that sort of critique be owing from? Is it a critique of labour? Is it a critique of Marxism or an argument for Marxism — proof positive that we sell our time and energy on a regularized basis so that we have the freedom to, well, continue doing the exact same thing: life as Groundhog Day. — One also can’t help but notice that the habitués of Funch’s photos are almost entirely living in their own interior worlds. Some are wearing earbuds. Some are nursing coffees. Some are… lost in time and space. But the one thing you can say quite positively is that in their heads, Funch’s subjects are practically anywhere except the space through which where their physical bodies are moving.

The corner of 42nd Street and Vanderbilt Avenue… what’s that? It’s a patch of nowhere that hides, like similar patches of nowhere, in all cities everywhere. It’s the space of Edward Hopper. It’s the real estate equivalent of a Styrofoam packing peanut. It’s blank, and it’s in this blankness that we circle back to Warhol and repetition and the aesthetic experience we enjoy when we look from one Marilyn to the next to see which screened face has what kind of silkscreen printing error.

— In many of the photos, the subjects are wearing the same out ts they wear in multiple photos. Our inner lm director is saying, wow, maybe these people should get a larger wardrobe.

How depressing that they go through their lives looking the same. But of course everyone’s a critic, and how many out ts are people supposed to have, anyway? Do these people live alone? Good! Because people living alone consume twice as much as do couples or families. Are they happy? Are they sad? Does it matter? They’re in a trance and so the contents of their frontal cortexes don’t matter. I think trance is the operative word here. A trance means you’re there but you’re not there. These people left their houses or apartments and are headed to work. At which point did they enter their trance… when they hit the snooze button? When they locked their front door? When they got on the subway? And when do they snap out of their trance… once they sit at their desks and check emails? When they eat lunch? Urban life looks very odd when you view it with a lens of presence. Maybe the subjects in these photos never leave their trance? Wouldn’t that be scary? Yet that’s most of civilized life… and Funch’s photos act as a detached yet empathetic critique of this thing we call capitalism and the way we package and sell ourselves and how we make our peace with our lots in life.

Peter Funch’s Website