For the longest time, you have been told that reality is something that can be bound by conventional standards. It has a height. It has a length. It has a width. It has a depth. For the longest time, we have agreed consciously or subconsciously to this general collective definition.

Well, the nineteenth century came along and it started casting into doubt the centrality of artistic truth as changes in how the human condition is approached, namely in innovations in psychoanalysis, psychology and cognitive sciences. We have started to look at reality from a psychological perspective differently.

Add to the mix Albert Einstein’s revolutionary ideas contained in the Theory of Relativity, and it becomes quite clear that reality is not what we assumed it to be. In fact, we have become so disconcerted, so fazed by the concept of multiple sources of reality and multiple judgments that we have reached a point where it really all boils down to individual point of view.

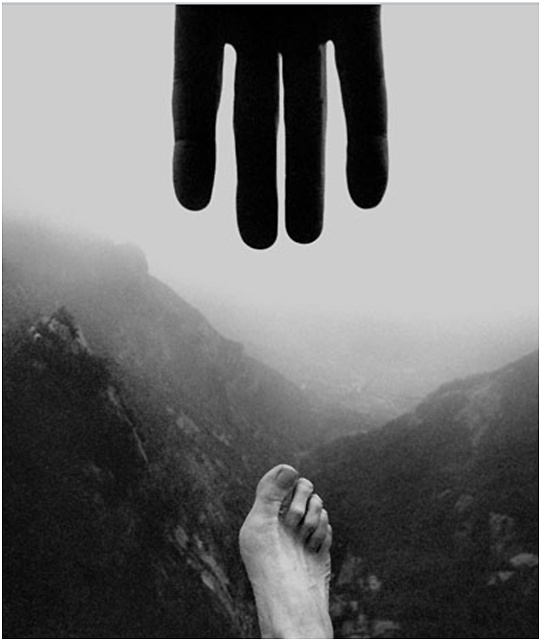

In the sciences, this is embodied by the Heisenberg principle. According to this principle, the moment you start observing any kind of phenomenon, you start changing it. Observation in of itself changes the phenomenon. Now, this is not some sort of philosophical or even quasi-metaphysical or even more distant mystical revelation. This is hard science. There are actual hard mathematical equations that prove this.

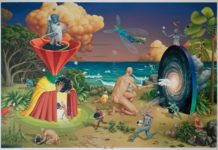

In fact, modern physics have all sorts of workarounds against the Heisenberg principle because you don’t want it to throw off whatever truth claims you come up with from your study. This is a big deal, and the artistic element of this played out in the 1920s but really reached ahead in the 1970s. In the 1920s, the idea that reality can only be represented a certain way was really starting to crumble.

If you took Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory and you created that work in, let’s say, the 1500s, there’s probably a good chance that you would at best gain the mild disapproval of art critics; at worst, you might find yourself burning at the stake because back then, if the authorities could not understand whatever ideas that you are championing, there’s a good chance they would be threatened so much by it that it can lead to severe risks to your physical safety.

Flash forward several hundred years and we’re in a completely different place. Now, the whole idea of truth is under assault. Whether you agree with this or not, it is the reality. Somebody’s truth is not necessarily somebody else’s truth because we are all looking at the same phenomenon from different perspectives. We have different experiences. We have different pasts.

All these differences add up to a tremendous amount of changes in how we perceive things, and the big difference from our mindset now from our mindset in the 1500s is that you’re not going to necessarily harm somebody or put somebody in some sort of outsider group because they have a different set of personal truths from you.

Of course, there is a logical limit to this. If you think that murder is perfectly okay, then there’s a problem because you’re going to be infringing on somebody else’s rights. You might kill other people or you might turn a blind eye when others kill each other. That seems to be the logical limit of this new postmodern ethic, which is harm. So, as long as nobody is harming each other, everybody is pretty much free to march their own tune.

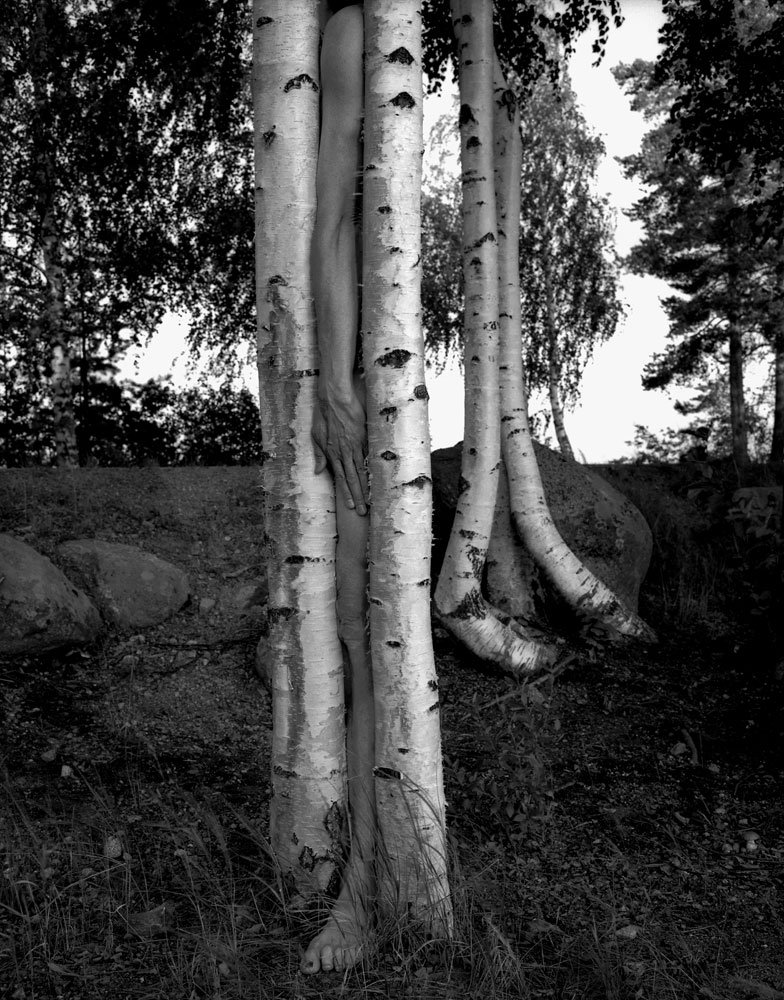

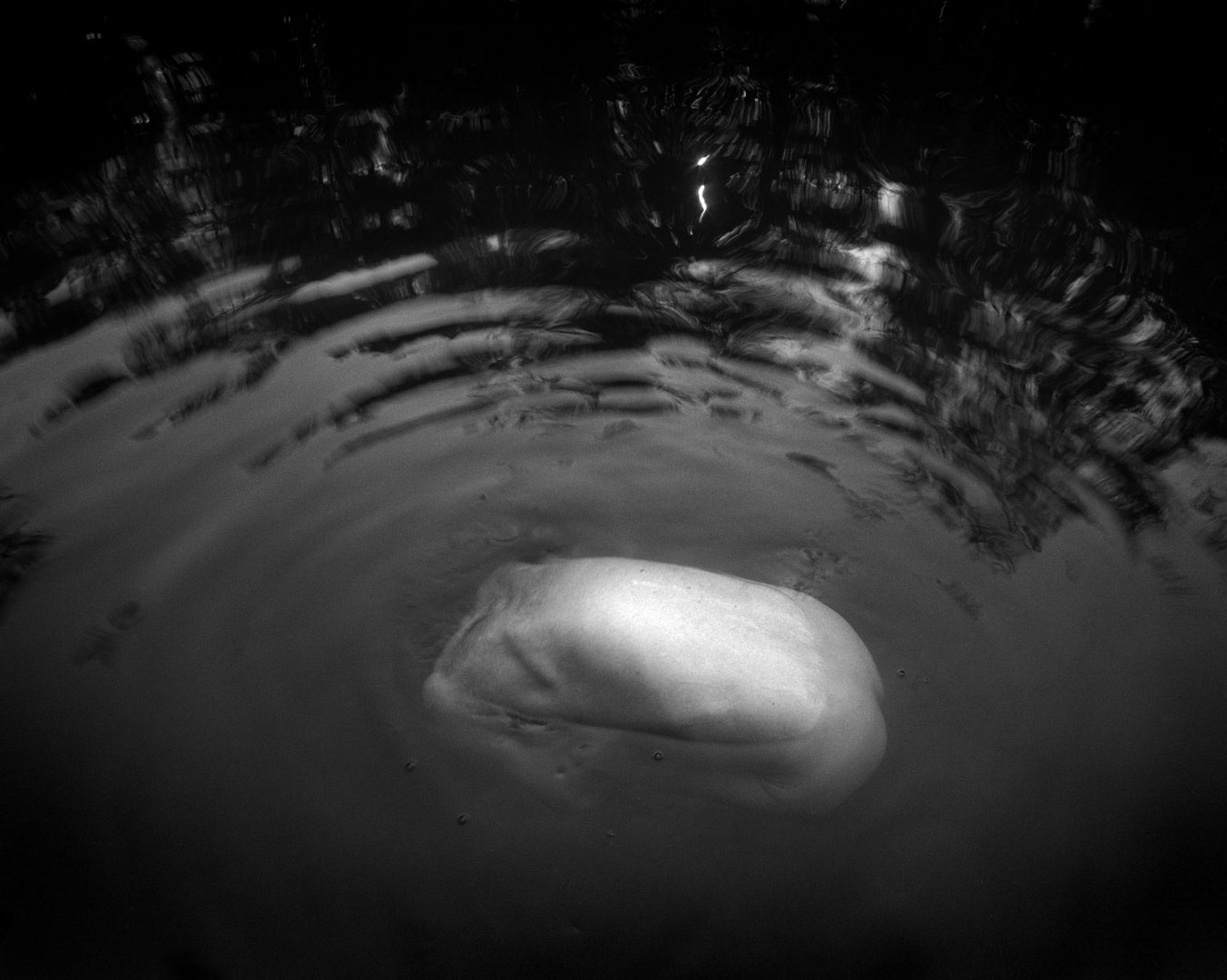

This is the spirit that really informs the work of Arno Rafael Minkkinen. It’s all about the internal realities that we walk around with and how we read these personal narratives and realities into the works of art and also the natural phenomena that we care to observe.

Arno Rafael Minkkinen’s Website